Користувач:Maximilian Bobko/Чернетка

| Б'ярке Інгелс | |

|---|---|

| Bjarke Bundgaard Ingels | |

| |

| Народження | 2 жовтня 1974 (50 років) Копенгаген, Данія |

| Навчання | Данська королівська академія витончених мистецтв |

Б'ярке Бундгаард Інгелс (дан. Bjarke Bundgaard Ingels, МФА: [ˈpjɑːkə ˈpɔnkɒ ˈe̝ŋˀl̩s]); (народився 2 жовтня 1974 року) — датський архітектор, засновник і креативний партнер Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG).

В Данії, Інгелс став відомим після створення двох житлових комплексів у Орестаді: VM Houses і Bjerget. У 2006 році він заснував Bjarke Ingels Group, яка станом на 2015 рік мала 400 співробітників. Компанія створила такі визначні проекти, як житловий комплекс Будинок-вісімка, VIA 57 West на Мангеттені, штаб-квартира Google в Північному Бейшорі (спільно з Томасом Хітервіком), парк Суперкілен і сміттєспалювальний завод Amager Bakke з лижним трампліном і стіною для скелелазіння на фасадах.

Починаючи з 2009 року, Інгелс виграв у численних архітектурних конкурсах. Він переїхав до Нью-Йорку в 2012 році, де BIG виграла архітектурний конкурс після урагану Сенді на вдосконалення системи запобігання затоплень Мангеттена, а зараз створює дизайн нової будівлі Другого всесвітнього торгового центру. У 2017 році про Інгелса і його компанію було знято документальний фільм BIG Time.

У 2011 році, Волл-стріт джорнел назвали Інгелса Інноватором року в архітектурі.[1], а в 2016 році журнал “Тайм” назвав його одним зі ста найвпливовіших людей".[2]

Народився в Копенгагені 1974 року, батько Інгелса — інженер а мати — дантист.[3] Hoping to become a cartoonist, he began studying architecture in 1993 at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, thinking it would help him improve his drawing skills. After several years, he began an earnest interest in architecture.[4] He continued his studies at the Escola Tècnica Superior d'Arquitectura in Barcelona, and returned to Copenhagen to receive his diploma in 1999.[5] As a third-year student in Barcelona, he set up his first practice and won his first competition.[6]

Alongside his architectural practice, Ingels has been a visiting professor at the Rice University School of Architecture, the Harvard Graduate School of Design,[7] the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation,[8] and most recently, the Yale School of Architecture.[9]

From 1998 to 2001, Ingels worked for Rem Koolhaas at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture in Rotterdam.[10] In 2001, he returned to Copenhagen to set up the architectural practice PLOT together with Belgian OMA colleague Julien de Smedt. The company received national and international attention for their inventive designs.[11] They were awarded a Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2004 for a proposal for a new music house for Stavanger, Norway.[12]

PLOT completed a 2 500 м2 (27 000 фут2) series of five open-air swimming pools, Islands Brygge Harbour Bath, on the Copenhagen Harbour front with special facilities for children in 2003.[13] They also completed Maritime Youth House, a sailing club and a youth house at Sundby Harbour, Copenhagen.[14]

The first major achievement for PLOT was the award-winning VM Houses in Ørestad, Copenhagen, in 2005. Inspired by Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation concept, they designed two residential blocks, in the shape of the letters V and M (as seen from the sky); the M House with 95 units, was completed in 2004, and the V House, with 114 units, in 2005.[15] The design places strong emphasis on daylight, privacy and views.[16] Rather than looking over the neighboring building, all of the apartments have diagonal views of the surrounding fields. Corridors are short and bright, rather like open bullet holes through the building. There are some 80 different types of apartment in the complex, adaptable to individual needs.[17] The building garnered Ingels and Smedt the Forum AID Award for the best building in Scandinavia in 2006.[18] Ingels lived in the complex until 2008 when he moved into the adjacent Mountain Dwellings.[16]

In 2005, Ingels also completed the Helsingør Psychiatric Hospital in Helsingør, a hospital which is shaped like a snowflake.[19][19] Each room of the hospital was specially designed to have a view, with two groups of rooms facing the lake, and one group facing the surrounding hills.[19]

After PLOT was disbanded at the end of 2005, in January 2006 Ingels made Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) its own company.[3] It grew to 400 employees by 2016.[11]

BIG began working on the 25-метрів-high (82 фут) Mountain Dwellings on the VM houses site in the Ørestad district of Copenhagen, combining 10 000 м2 (110 000 фут2) of housing with 20 000 м2 (220 000 фут2) of parking and parking space, with a mountain theme throughout the building.[20] The apartments scale the diagonally sloping roof of the parking garage, from street level to 11th floor, creating an artificial, south facing 'mountainside' where each apartment has a terrace measuring around 93 м2 (1 000 фут2).[16] The parking garage contains spots for 480 cars.[21] The space has up to 16-метрів-high (52 фут) ceilings, and the underside of each level of apartments is covered in aluminium painted in a distinctive colour scheme of psychedelic hues which, as a tribute to Danish 1960s and '70s furniture designer Verner Panton, are all exact matches of the colours he used in his designs.[22] The colours move, symbolically, from green for the earth over yellow, orange, dark orange, hot pink, purple to bright blue for the sky.[22] The northern and western facades of the parking garage depict a 3 000 м2 (32 000 фут2) photorealistic mural of Himalayan peaks.[21] The parking garage is protected from wind and rain by huge shiny aluminium plates, perforated to let in light and allow for natural ventilation. By controlling the size of the holes, the sheeting was transformed into the giant rasterized image of Mount Everest.[20] Completed in October 2008, it received the World Architecture Festival Housing Award (2008), Forum AID Award (2009) and the MIPIM Residential Development Award at Cannes (2009).[12] Dwell magazine has stated that the Mountain Dwellings "stand as a beacon for architectural possibility and stylish multifamily living in a dense, design-savvy city."[16]

Their third housing project, 8 House, commissioned by Store Frederikslund Holding, Høpfner A/S and Danish Oil Company A/S in 2006 and completed in October 2010, was the largest private development ever undertaken in Denmark and in Scandinavia, combining retail with commercial row houses and apartments.[23][24] It is also Ingels' third housing development in Ørestad, following VM Houses and Mountain Dwellings.[25] The sloping, bow-shaped 10-storey building consists of 61 000 м2 (660 000 фут2) of three different types of residential housing and 10 000 м2 (110 000 фут2) of retail premises and offices, providing views over the fields and marches of Kalvebod Faelled to the south. The 476-unit apartment building forms a figure 8 around two courtyards.[3] Noted for its green roof which won it the 2010 Scandinavian Green Roof Award, Ingels explained, "The parts of the green roof that remain were seen by the client as integral to the building as they are visible from the ground. These not only provide the environmental benefits that we all know come from green roofs, but also add to the visual drama and appeal of the sloping roofs and rooftop terrace in between."[26] The building also won the Best Residential Building at the 2011 World Architecture Festival,[27] and the Huffington Post included 8 House as one of the "10 Best Architecture Moments of 2001–2010."[28]

In 2007, Ingels exhibited at the Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York City and was commissioned to design the Danish Maritime Museum in Helsingør. The current museum is located on the UNESCO World Heritage Site of nearby Kronborg Castle.[29] The concept of the building is 'invisible' space, a subterranean museum which is still able to incorporate dramatic use of daylight.[30] In launching the $40 million project, BIG had to reinforce an abandoned concrete dry dock on the site, 150 метрів (490 фут) long, 25 метрів (82 фут) wide and 9 метрів (30 фут) deep, building the museum on the periphery of the reinforced dry dock walls which will form the facade of the new museum.[30] [31] The dry dock will also host exhibitions and cultural events throughout the year.[30] The museum's interior is designed to simulate the ambiance of a ship's deck, with a slightly downward slope. The 7 600 м2 (82 000 фут2) exhibition gallery is to house an extensive collection of paintings, model ships, and historical equipment and memorabilia from the Danish Navy.[30] Ingels is collaborating with consulting engineer Rambøll, Alectia for project management, and E. Pihl & Søn and Kossmann.dejong for construction and interior design.[29] Some 11 different foundations are funding the project. Construction began on the museum in September 2010 and it is scheduled for completion by the summer of 2013.[30] In September 2012, the Kronborg and Zig-Zag Bridge components to the building were shipped in from China.[30]

Ingels designed a pavilion in the shape of a loop for the Danish World Expo 2010 pavilion in Shanghai. The open-air 3 000 м2 (32 000 фут2) steel pavilion has a spiral bicycle path, accommodating up to 300 cyclists who experience Danish culture and ideas for sustainable urban development.[32] In the centre, amid a pool of 1 million litres (264,172 gallons) of water, is the Copenhagen statue of The Little Mermaid, paying homage to Danish author Hans Christian Andersen.[32]

In 2009, Ingels designed the new National Library of Kazakhstan in Astana located to the south of the State Auditorium, said to resemble a "giant metallic doughnut".[33] BIG and MAD designed the Tilting Building in the Huaxi district of Guiyang, China, an innovative leaning tower with six facades.[16] Other projects included the city hall in Tallinn, Estonia, and the Faroe Islands Education Centre in Torshavn, Faroe Islands.[11] Accommodating some 1,200 students and 300 teachers, the facility has a central open rotunda for meetings between staff and pupils.[34]

In 2010, Fast Company magazine included Ingels in its list of the 100 most creative people in business, mentioning his design of the Danish pavilion.[35] BIG projects became increasingly international, including hotels in Norway, a museum overlooking Mexico City, and converting an oil industry wasteland into a zero-emission resort on Zira Island off the coast of Baku, Azerbaijan.[36] The 1 000 000 м2 (11 000 000 фут2) resort started construction in 2010, and represented the seven mountains of Azerbaijan. It was cited as "one of the world's largest eco-developments."[37] The "mountains" were covered with solar panels and provide for residential and commercial space. According to BIG, "The mountains are conceived not only as metaphors, but engineered as entire ecosystems, a model for future sustainable urban development".[37]

In 2011, BIG won a competition to design the roof of the Amagerforbrænding industrial building, with 31 000 м2 (330 000 фут2) of ski slopes of varying skill levels.[38] The roof is put forward as another example of "hedonistic sustainability": designed from recycled synthetics, aiming to increase energy efficiency by up to 20 percent.[39] In October 2011, The Wall Street Journal named Ingels the Innovator of the Year for architecture,[40] later saying he was "becoming one of the design world's rising stars" in light of his portfolio.[41]

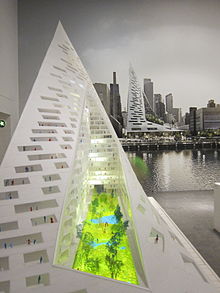

In 2012, Ingels moved to New York to supervise work on a pyramid-like apartment building on West 57th Street,[3] a collaboration with real estate developer Durst Fetner Residential.[42] BIG opened a permanent New York office, and became committed to further work in New York. By mid-2012 that office had a staff of 50, which they used to launch other projects in North America.[41][43][44][45][46] In 2014 Ingels's design for an integrated flood protection system, the DryLine, was a winner of the Rebuild By Design competition created by the Department of Housing and Urban Development in the wake of Hurricane Sandy.[47] The DryLine will stretch Manhattan's shoreline on the Lower East Side, with a landscaped flood barrier in East River Park, enhanced pedestrian bridges over the FDR drive, and permanent and deployable floodwalls north of East 14th Street.[48]

BIG designed the Lego House that began construction in 2014 in Billund, Denmark. Ingels said of it, "We felt that if BIG had been created with the single purpose of building only one building, it would be to design the house for Lego."[49] Designed as a village of interlocking and overlapping buildings and spaces, the house is conceived with identical proportions to the toy bricks, and can be constructed one-for-one in miniature. They also designed the Danish Maritime Museum in Elsinore, Denmark, and a master plan for the new Smithsonian Institution south campus in Washington, D.C. This is part of a 20-year project that will begin in 2016.[50][51]

Ingels also designed two extensions for his former High School in Hellerup, Denmark — a handball court, and a larger arts and sports extension. The handball court, in homage to the architect's former math teacher, sports a roof with curvature that traces the trajectory of a thrown handball.[52]

In 2015, Ingels began working on a new headquarters for Google in Mountain View, California with Thomas Heatherwick, the British designer. Bloomberg Businessweek hailed the design as "The most ambitious project unveiled by Google this year ..." in a feature article on the design and its architects.[53] Later that year, BIG was chosen to take up the design of Two World Trade Center, one of the towers replacing the Twin Towers. The work had initially been entrusted to the British firm Foster and Partners, but was revoked and given back to Foster in 2019. [54][55][56]

Ingels was considered for the Hudsons Yard project.[57] In late 2016, the project became official.[58]

In 2009, Ingels became a co-founder of the KiBiSi design group, together with Jens Martin Skibsted and Lars Larsen. With its focus on urban mobility, architectural illumination and personal electronics, the company designs bicycles, furniture, household objects and aircraft, becoming one of Scandinavia's most influential design groups.[59] KiBiSi designed the furniture for Ingels' Danish Pavilion at EXPO 2010.[60]

Ingels's first book, Yes Is More: An Archicomic on Architectural Evolution,[61] catalogued 30 projects from his practice. Designed in the form of a comic book, which he believed was the best way to tell stories about architecture, he later said that the medium contributed to the perception that some of his projects are cartoonish.[4][62] A sequel, Hot to Cold: An Odyssey of Architectural Adaptation, explored 60 case studies through a climatic lens, to examine where and how people live on the planet, working from the warmest regions to the coldest. The book was designed by Grammy Award-winning designer Stefan Sagmeister, and accompanied by an exhibition of the same name at the National Building Museum in Washington D.C. The book featured well known projects such as VIA (West 57th), Amager Bakke, 8 House, Gammel Hellerup High School, Superkilen, The Lego House and the Danish Maritime Museum, amongst others.[63]

In 2009, Ingels spoke at a TED event in Oxford, UK.[64] He presented the case study "Hedonistic sustainability" in a workshop on managing complexity at the 3rd International Holcim Forum 2010 in Mexico City, and was a member of the Holcim Awards regional jury for Europe in 2011.[65]

In 2015, a division of the Kohler Company, Kallista, released a new line of bath and kitchen products designed by Ingels. Named "taper", the fixtures featured minimalist and mid-century Danish design.[66]

In 2016, he was a keynote speaker at the leadership conference Aarhus Symposium, in which he addressed the role of creativity and empowerment in leadership.[67]

Ingels was cast in My Playground, a documentary film by Kaspar Astrup Schröder that explores parkour and freerunning, with much of the action taking place on and around BIG projects.[68]

He was also part of the documentary film Genre de Vie, about bicycles, cities and personal awareness. It looks at desired space and our own impact to the process of it. The film documents urban life empowered by the simplicity of the bicycle.

Ingels was profiled in the first season of the Netflix docu-series Abstract: The Art of Design.[69]

—Bjarke Ingels.[70]

In 2009, The Architectural Review said that Ingels and BIG "has abandoned 20th-century Danish modernism to explore the more fertile world of bigness and baroque eccentricity... BIG's world is also an optimistic vision of the future where art, architecture, urbanism and nature magically find a new kind of balance. Yet while the rhetoric is loud, the underlying messages are serious ones about global warming, community life, post-petroleum-age architecture and the youth of the city."[71] The Netherlands Architecture Institute described him as "a member of a new generation of architects that combine shrewd analysis, playful experimentation, social responsibility and humour."[72]

In an interview in 2010, Ingels provided a number of insights on his design philosophy. He defines architecture as "the art of translating all the immaterial structures of society – social, cultural, economical and political – into physical structures." Architecture should "arise from the world" benefiting from the growing concern for our future triggered by discussion of climate change. In connection with his BIG practice, he explains: "Buildings should respond to the local environment and climate in a sort of conversation to make it habitable for human life" drawing, in particular, on the resources of the local climate which could provide "a way of massively enriching the vocabulary of architecture."[4]

Luke Butcher noted that Ingels taps into metamodern sensibility, adopting a metamodern attitude; but he "seems to oscillate between modern positions and postmodern ones, a certain out-of-this-worldness and a definite down-to-earthness, naivety and knowingness, idealism and the practical."[70] Sustainable development and renewable energy are important to Ingels, which he refers to as "hedonistic sustainability". He has said that "It's not about what we give up to be sustainable, it's about what we get. And that is a very attractive and marketable concept." [73] He has also been outspoken against "suburban biopsy" in Holmen, Copenhagen, caused by wealthy older people (the grey-gold generation) living in the suburbs and wanting to move into the town to visit the Royal Theatre and the opera.[74]

In 2014, Ingels released a video entitled 'Worldcraft' as part of the Future of StoryTelling summit, which introduced his concept of creating architecture that focuses on turning "surreal dreams into inhabitable space".[75] Citing the power of alternate reality programs and video games, like Minecraft,[76] Ingels's 'worldcraft' is an extension of 'hedonistic sustainability' and further develops ideas established in his first book, Yes Is More. In the video (and essay by the same name in his second book, Hot to Cold: An Odyssey of Architectural Adaptation) Ingels notes: "These fictional worlds empower people with the tools to transform their own environments. This is what architecture ought to be ..." "Architecture must become Worldcraft, the craft of making our world, where our knowledge and technology doesn't limit us but rather enables us to turn surreal dreams into inhabitable space. To turn fiction into fact."[77]

In 2015, Ingels bought an apartment in New York's Dumbo neighborhood. In 2016, Ingels met his girlfriend, Spanish architect Ruth Otero, at Burning Man.[62]

- For a full list of projects, see Bjarke Ingels Group#Completed projects

- Islands Brygge Harbour Bath, Copenhagen (completed 2003)

- VM Houses, Ørestad, Copenhagen (completed 2005)

- Mountain Dwellings, Ørestad, Copenhagen (completed 2008)

- Danish Maritime Museum, Helsingør, Denmark (u/c, completion mid-2013)

- 8 House, Ørestad, Copenhagen (completed 2010)

- Superkilen, a public park in Copenhagen (completed 2011).[78]

- Amager Bakke, incinerator power plant and ski hill (2017 completion)

- Europa City, Paris

- Two World Trade Center New York City, office building (On hold, Larry Silverstein is in talks with News Corporation and 21st Century Fox to create a joint headquarters.)[джерело?]

- 2007 BIG City, Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York[79]

- 2009 Yes is More, Danish Architecture Centre, Copenhagen[80][81]

- 2010 Yes is More, CAPC, Bordeaux and WECHSELRAUM, Stuttgart

- 2015 Hot to Cold: An Odyssey of Architectural Adaptation, National Building Museum

- 2019-2020 BIG presents FORMGIVING, Danish Architecture Centre, Copenhagen

- For a more detailed list of awards, see Bjarke Ingels Group#Awards

- 2001 and 2003 Henning Larsen Prize[82]

- 2002 Nykredit Architecture Prize

- 2004 ar+d award for the Maritime Youth House[83]

- 2004 Golden Lion for best concert hall design, Venice Biennale of Architecture (for Stavanger Concert Hall proposal)

- 2006 Forum AID Award, Best Building in Scandinavia in 2006 (for VM Houses)

- 2007 Mies van der Rohe Award Traveling Exhibition – VM Houses

- 2008 Forum AID Award for Best Building in Scandinavia in 2008 (for Mountain Dwellings)

- 2009 ULI Award for Excellence (for Mountain Dwellings)[84]

- 2010 European Prize for Architecture[85]

- 2011 Dreyer Honorary Award

- 2011 Danish Crown Prince Couple's Culture Prize[86]

- 2011 French Academy of Architecture, Prix Delarue Award

- 2011 The Wall Street Journal Architectural Innovator of the Year Award

- 2012 American Institute of Architects Honor Award for 8 House, deemed to elevate the quality of architectural practice.[87]

- 2013 Den Danske Lyspris (for Gammel Hellerup Gymnasium)

- 2013 International Olympic Committee Award, Gold Medal (for Superkilen)[джерело?]

- 2013 American Institute of Architects Honor Award, Regional and Urban Design (for Superkilen)

- 2014 European Prize of Architecture Philippe Rotthier (for the Danish Maritime Museum)

- 2014 Urban Land Institute, 40 Under 40 Award

- 2015 Global Holcim Awards for Sustainable Construction, Bronze (for The DryLine resiliency project)[88]

- 2017 C.F. Hansen Medal[89]

- Bjarke Ingels, Yes is More: An Archicomic on Architectural Evolution (exhibition catalogue), Copenhagen, 2009, ISBN 9788799298808[81]

- BIG, Bjarke Ingels Group Projects 2001–2010, Design Media Publishing Ltd, 2011, 232 pages. ISBN 9789881973863.

- BIG, BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group, Archilife, Seoul, 2010, 356 pages. ISBN 9788996450818

- BIG, BIG: Recent Project, GA Edita, Tokyo, 2012. ISBN 9784871406789

- BIG, Abitare, Being BIG, Abitare, Milan, 2012.

- BIG, Arquitectura Viva, AV Monograph BIG, Arquitectura Viva, Madrid, 2013. ISBN 9788461655922

- BIG, Topotek & Superflex, Barbara Steiner, Superkilen, Arvinius + Orfeus, Stockholm, 2013, 224 Pages. ISBN 9789187543029

- BIG, Bruce Peter, Museum in the Dock, Arvinius + Orfeus, Stockholm, 2014, 208 pages. ISBN 9789198075649

- Bjarke Ingels, Hot to Cold: An Odyssey of Architectural Adaptation (exhibition catalogue), Taschen, New York and Köln, 2015, 712 pages. ISBN 9783836557399[63]

- ↑ Woodward, Richard B. (28 October 2011). Building a Better Future. Wall Street Journal. Процитовано 21 October 2019.

- ↑ Західний кр й оза В.Г. Па-

- ↑ а б в г Ian Parker, "High Rise", The New Yorker, 10 September 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ а б в Ellen Bokkinga, "Bjarke Ingels: a BIG architect with a mission" [Архівовано 6 December 2012 у Wayback Machine.], TedX Amsterdam Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ "Barje Ingels: The European Prize for Architecture", Urbanscraper. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ Blå Blog: Bjarke Ingels. Dansk Arkitektur Center. Архів оригіналу за 13 February 2012. Процитовано 12 October 2012.

- ↑ Judges 2009 – Bjarke Ingels. World Architecture Festival. Архів оригіналу за 26 February 2012. Процитовано 12 October 2012.

- ↑ Invitation – Press Release (PDF). Student Housing, International Competition for Architects up to 35. Процитовано 12 October 2012.

- ↑ Karl Schmeck, "Midterm at Yale’s BIG/Durst Studio", MetropolisMag.com. 24 March 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ "Bjarke Ingels: Architect", Ted.com. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ а б в Vladimir Belogolovsky, "One-on-One: Architecture as a Social Instrument: Interview with Bjarke Ingels of BIG", ArchNewsNow, 1 March 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ а б "Ingels to Address NSAD Students on Feb. 25 at the Museum of Natural History in San Diego" [Архівовано 9 July 2012 у Wayback Machine.], New School of Architecture + Design. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ "Harbour Bath in Islands Brygge" [Архівовано 12 March 2011 у Wayback Machine.], Architecture News Plus. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ "Maritime Youth House" [Архівовано 30 October 2012 у Wayback Machine.], Architecture News Plus. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ "VM Houses: 230 Dwellings in Ørestad"[недоступне посилання з 01.06.2019], Architecture News Plus. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ а б в г д Dwell. Dwell, LLC. September 2009. с. 87. ISSN 1530-5309.

- ↑ "VM Houses / PLOT = BIG + JDS", Arch Daily. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ Vladimir Belogolovsky, "One-on-One: Architecture as a Social Instrument: Interview with Bjarke Ingels of BIG", ArchNewsNow.com, 1 March 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ а б в A hospital where every room has a view. World Architecture News. 31 March 2009. Архів оригіналу за 29 February 2012. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ а б Think Big. Dwell Magazine. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ а б Making a Mountain. Metropolis Magazine. 17 December 2008. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ а б The Mountain Dwellings. Icon Eye Magazine. October 2008. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ 8 House. arcspace. Процитовано 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "Housing winner: 8 House, Denmark" [Архівовано 30 August 2012 у Wayback Machine.], World Architecture Festival. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "8 House / BIG", Arch Daily. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ BIG's 8 House in Copenhagen wins the 2010 Scandinavian Green Roof Award. World Architecture News. 18 August 2010. Архів оригіналу за 25 August 2012. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ "Day two winners announced" [Архівовано 14 November 2011 у Wayback Machine.], World Architecture Festival. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ Jacob Slevin, "10 Best Architecture Moments of 2001–2010", Huffington Post, 23 December 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ а б The new Danish Maritime Museum. Danish Maritime Museum. Архів оригіналу за 4 November 2011. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ а б в г д е Danish Maritime Museum, Denmark. Design Build Network. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ Big Group.(Culture). The Architectural Review via HighBeam Research

(необхідна підписка). 1 May 2008. Архів оригіналу за 26 January 2013. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

(необхідна підписка). 1 May 2008. Архів оригіналу за 26 January 2013. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ а б Opening shot. PM Network via HighBeam Research

(необхідна підписка). 1 August 2010. Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 9 June 2012.

(необхідна підписка). 1 August 2010. Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 9 June 2012.

- ↑ Mayhew, Bradley; Bloom, Greg; Clammer, Paul (1 November 2010). Central Asia. Lonely Planet. с. 177. ISBN 978-1-74179-148-8. Процитовано 10 October 2012.

- ↑ Hillside school sports exciting shape. Building Design & Construction via HighBeam Research

(необхідна підписка). 19 September 2004. Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 9 June 2012.

(необхідна підписка). 19 September 2004. Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 9 June 2012.

- ↑ "#64 Bjarke Ingels" [Архівовано 16 November 2012 у Wayback Machine.], Fast Company. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ Zira Island Masterplan. World Architecture News. Архів оригіналу за 15 April 2009. Процитовано 30 April 2009.

- ↑ а б Brass, Kevin (20 March 2009). Carbon-neutral 'peaks' in the Caspian Sea Weekly. International Herald Tribune via HighBeam Research

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ BIG Puts a Ski Slope on Copenhagen's New Waste-to-Energy Plant. Bustler. Процитовано 12 October 2012.

- ↑ Amagerforbrænding waste-to-energy facility. Ramboll. Архів оригіналу за 5 May 2013. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ "WSJ 2011 Innovator Awards: Architecture", WSJ Magazine, 27 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ а б Robbie Whelan, "New Face of Design", The Wall Street Journal, 22 July 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ Li, Roland (20 July 2011). Back in business: appetite for new condos returning to market. Real Estate Weekly via HighBeam Research

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ Li, Roland (1 March 2011). BIG lease at Starrett-Lehigh. Real Estate Weekly via HighBeam Research

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 3 January 2013. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 3 January 2013. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ Ditmars, Hadani (1 September 2012). Letter from Vancouver: with its population expected to double by 2050, the city is finally facing up to its future, says Hadani Ditmars. The Architectural Review via HighBeam Research

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 3 January 2013. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 3 January 2013. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ ST. PETERSBURG PIER DESIGN PANEL NARROWS LIST OF APPLICANTS TO 9 SEMI-FINALISTS. US Fed News Service, Including US State News via HighBeam Research

(необхідна підписка). 31 July 2011. Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

(необхідна підписка). 31 July 2011. Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY'S MILLER GALLERY PRESENTS US PREMIERE OF "IMPERFECT HEALTH: THE MEDICALIZATION OF ARCHITECTURE"-CARNEGIE MELLON NEWS – CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY. States News Service via HighBeam Research

(необхідна підписка). 27 July 2012. Архів оригіналу за 28 May 2014. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

(необхідна підписка). 27 July 2012. Архів оригіналу за 28 May 2014. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ Rebuild by Design – Finalists. Rebuildbydesign.org. Процитовано 14 July 2015.

- ↑ NYC Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency. Nyc.gov. 11 June 2013. Процитовано 14 July 2015.

- ↑ Hot to Cold: An Odyssey of Architectural AdaptationTaschen, 2015

- ↑ bjarke ingels group reveals smithsonian masterplan for washington DC. designboom.com. 13 November 2014. Процитовано 14 August 2015.

- ↑ History, Travel, Arts, Science, People, Places | Smithsonian. Smithsonianmag.com. Процитовано 14 July 2015.

- ↑ Gammel Hellerup Gymnasium / BIG. ArchDaily. 7 August 2013. Процитовано 14 July 2015.

- ↑ Stone, Brad (7 May 2015). Google's New Campus: Architects Ingels, Heatherwick's Moon Shot – Bloomberg Business. Bloomberg.com. Процитовано 14 July 2015.

- ↑ Lucie Rychla (4 June 2014). Danish architects to design World Trade Center skyscraper number two. Copenhagen Post. Архів оригіналу за 18 September 2017. Процитовано 5 June 2015.

- ↑ Speiser, Matthew (11 June 2015). The final building at the World Trade Center will look like a 'vertical village of city blocks,' says architect. Business Insider. Процитовано 13 June 2015.

- ↑ Clarke, Katherine (11 June 2015). World Trade Center starchitect Bjarke Ingels would have built the twin towers back the way they were. New York Daily News. Процитовано 13 June 2015.

- ↑ Top 10 biggest real estate projects coming to NYC. 10 October 2016. Процитовано 2 October 2018.

- ↑ Bjarke Ingels's Hudson Yards skyscraper is officially moving forward. 29 September 2016. Процитовано 2 October 2018.

- ↑ "Speaker: Bjarke Ingels", Design Indaba. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ Designwire.(KiBiSi launched). Interior Design. 1 January 2010. Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 14 October 2012 — через HighBeam Research.

- ↑ Ingels, Bjarke (2009). Yes Is More: An Archicomic on Architectural Evolution. Taschen America LLC. ISBN 978-3-8365-2010-2. Процитовано 8 October 2012.

- ↑ а б Binelli, Mark (14 September 2016). Meet Architect Bjarke Ingels, the Man Building the Future. Rolling Stone. Процитовано 14 September 2016.

- ↑ а б Ingels, Bjarke (2015). BIG, HOT TO COLD: An Odyssey of Architectural Adaptation: Bjarke Ingels: 9783836557399: Amazon.com: Books. ISBN 978-3836557399.

- ↑ "TED Conference Program 2009", TED Global. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- ↑ "Holcim Awards Webpage", Holcim Foundation. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ↑ Shuhei Senda (20 August 2015). bjarke ingels designs his first line of bath + kitchen products for kallista. Designboom.com. Процитовано 3 September 2015.

- ↑ The Art of Power. Aarhus Symposium. Архів оригіналу за 3 October 2018. Процитовано 2 October 2018.

- ↑ My Playground. Team JiYo. Процитовано 19 October 2012.

- ↑ Netflix launches new documentary series Abstract: The Art of Design with a stellar lineup. Itsnicethat.com. 19 January 2017. Процитовано 2 October 2018.

- ↑ а б Bjarke Ingels Group. Metamodernism. 14 January 2011. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ Edwards, Brian (1 May 2009). Bigness and baroque eccentricity.(Yes is More)(. The Architectural Review via HighBeam Research

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 25 January 2013. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 25 January 2013. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ "Lecture: Bjarke Ingels. Hedonistic Sustainability". Netherlands Architecture Institute. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ Torres, Andrew (1 January 2012). A Time to Reassert. Middle East Interiors via HighBeam Research

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

(необхідна підписка). Архів оригіналу за 24 September 2015. Процитовано 14 October 2012.

- ↑ Stensgaard, Pernille; Schaldemose, Anne Prytz (2006). Copenhagen: People and Places. Gyldendal A/S. с. 183. ISBN 978-87-02-04672-4. Процитовано 10 October 2012.

- ↑ Worldcraft: Bjarke Ingels (Future of StoryTelling 2014). YouTube. 9 September 2014. Процитовано 14 July 2015.

- ↑ 11 Games Like Minecraft You Should Try | GamesLike.com. www.gameslike.com (амер.). Процитовано 25 серпня 2017.[недоступне посилання з 01.10.2019]

- ↑ Architecture should be more like Minecraft, says Bjarke Ingels. Dezeen.com. 26 January 2015. Процитовано 14 July 2015.

- ↑ Bonnie Fortune, "So many people lent a hand to give us parklife!" [Архівовано 5 April 2013 у Wayback Machine.], Copenhagen Post, 15 January 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ LEGO Towers by Bjarke Ingels Group. Dezeen. 10 September 2007. Процитовано 12 October 2012.

- ↑ Yes is More. Danish Architecture Centre. Архів оригіналу за 5 June 2009. Процитовано 12 October 2012.

- ↑ а б Yes is More: An Archicomic on Architectural Evolution' by Bjarke Ingels. dsgn world. Архів оригіналу за 23 June 2012. Процитовано 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "Bjarke Ingels" [Архівовано 4 November 2016 у Wayback Machine.], Mapolis: Architecture. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "Maritime Youth House : Nye Bygning i København", e-architect. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ Urban Land Institute presents Award of Excellence to the Mountain. +MOOD. Архів оригіналу за 9 August 2009. Процитовано 12 October 2012.

- ↑ Lene Tranberg, Hon. FAIA. American Institute of Architects. Процитовано 12 October 2012.

- ↑ Kronprinsparrets Priser (Danish) . Bikubenfonden. Архів оригіналу за 6 October 2014. Процитовано 28 September 2014.

- ↑ "AIA Award 2012 for BIG's 8 House" [Архівовано 25 May 2014 у Wayback Machine.], DAC. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ↑ Winners - Global Holcim Awards Winners 2015.

- ↑ Bjarke Ingels: Motivering for medaljemodtagelse (Danish) . Akademieraadet. 2017. Архів оригіналу за 30 March 2017. Процитовано 27 February 2018.

- Maximilian Bobko/Чернетка на TED(англ.)

- Bjarke Ingels design consultancy KiBiSi.com

- 'Yes is More' Talk at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), London 2010 (video)

- Bjarke interviewed for Studio Banana

- Interview with Bjarke Ingels Archi-Ninja.com

- Google Campus

У білоруській мові українізми відомі з XV століття. Вони полягали у змішанні и — ы (печаты(и), влади(ы)ка); ѣ—и (види(ѣ)ти, терпи(ѣ)ти).

Трапляються в пам'ятках стародавнього періоду, що виникли на основі українських джерел, наприклад «Четьї-Мінеї» (1489). Збагачення білоруської лексики найбільш інтенсивно відбувалося з 1-ї половини XVII ст. (Після переміщення центру православної культури з Вільнюса в Київ), через пам'ятки, створені на сусідній з українськими землями південно-західній території сучасної Білорусі, наприклад, Мозирський список «Олександрії» (1697), Московський (біл.) список «Діаріуша» Афанасія Пилиповича (1638-1648).

Проникненню в білоруську мову українізмів сприяли письменники, які походили з України, але створювали свої твори на білоруських землях, наприклад «Євангеліє учительне» (1616) і «Сказання похвальне» (1620) Мелетія Смотрицького. В деякі білоруські пам'ятки потрапляли слова з українською огласовкою (котрий, що, сокира), а також лексичні та словотвірні українізми (бучный — біл. раскошны, зволокати — біл. адцягваць, марудзіць, прохати — біл. прасіць, шадок — біл. нашчадак).

У 1920-ті роки при розробці наукової термінології деякі терміни білоруської мови були створені за українськими зразками: суспільно-політичні (барацьба, барацьбіт), лінгвістичні (дзеяслоў, дзеепрыметнік, займеннік, дзеепрыслоўе, чаргаванне).

Лексичні українізми, пов'язані з позначенням специфічно українських (сучасних та історичних) реалій, зберігаються в перекладах з української мови. Наприклад, в перекладах Янки Купали творів Тараса Шевченка на білоруську мову трапляються українізми байдак, байрак, гайдамак, кабзар тощо. Традиції української мови виявилися найбільш стійкими в білоруській народно-розмовній мові (західний діалект білоруської мови), ніж в літературній мові: доня — біл. дачка, худоба — біл. жывёла.

Білоруська мова належить до східної групи слов'янської гілки індоєвропейської родини мов. Згідно зі списком Сводеша для слов'янським мов, найближче українська споріднена з білоруською мовою (190 збігів з 207), російською (172 збігів з 207), а також польською (169 збігів з 207).

Росіянізми, як запозичення широко представлені в білоруській мові, що обумовлено структурною близькістю двох мов. У білоруській мові серед запозичень з російської мови виділяють безпосередні русизми і слова, запозичені з інших мов за посередництвом російської мови. Вживання росіянізмів у мовленні спричинене інтерференцією або цільовою установкою носія мови. Найчастіше росіянізми спостерігаються як факти інтерференції в усній мові білорусько-російських білінгвів[1].

Поліське (або Прип'ятське) льодовикове озеро — гіпотетичне доісторичне озеро, яке існувало на території Поліської низовини, між південною межею льодовика та кряжами льодовикових фронтальних морен.

- ↑ БЭ. Т. 13. — Мінськ, 2001, ст. 457.

Поліське (або Прип'ятське) льодовикове озеро — гіпотетичне доісторичне озеро, яке існувало в пізньому плейстоцені на території Поліської низовини, між південною межею льодовика та кряжами льодовикових фронтальних морен.

На території України фінальний палеоліт розпочався катастрофічним потоком із Поліського озера, що прокотився долиною Дніпра до Чорного моря. Закінчився фінальний палеоліт відомою Білінгенською катастрофою, коли близько 10 300 років тому за некаліброваною шкалою холодне Балтійське прильодовикове озеро прорвало крижану греблю в районі Данських проток. Унаслідок раптового зникнення величезного Балтійського холодного басейну сталося різке потепління, і в Європі сформувався сучасний помірний клімат. Швидке танення льодовиків у фінальному плейстоцені створило умови для стоку води з сучасної долини Прип’яті не на схід, у Дніпро, а на захід — у басейн Західного Бугу, а також сприяло утворенню в басейні Прип’яті замкненого озера. Цю ідею розвивав П. А. Тутковський, який звернув увагу на поширення в Поліссі озерних відкладів і розробив концепцію озерних лесів.[1] У другій половині ХХ ст. білоруські дослідники М. М. Цапенко[2] та О. П. Мандер[3], спираючись на геологічні дані щодо наявності потужних плейстоценових озерних відкладів в басейні Прип’яті, визначили приблизні межі Поліського озера, що мало стік у басейн Західного Бугу в напрямку від Пінська до Берестя. На сході озеро підпружувалося в районі Мозира моренним пасмом дніпровського зледеніння. За визначенням згаданих білоруських дослідників, останній прорив озера в долину Дніпра стався наприкінці валдайського зледеніння. Сліди цього прориву М. М. Цапенко відшукав за 20 км на південний схід від Мозира, біля білоруського села Юровичі на нижній Прип’яті.[4]

Західний край озера В. Г. Пазинич розміщує у районі нижньої течії Стоходу, де абсолютна висота сягає 143 м над рівнем моря, з якої відбувався стік надлишків озерної води у Західний Буг. Окресливши межі водойми за цією гіпсометричною відміткою, дослідник отримав приблизні межі озера: 300 км із заходу на схід (від гирла Стоходу до с. Юровичі) та 130 км у меридіональному напрямку за максимальної глибини понад 20 м у східній частині водойми. Отже, озеро було відносно неглибоким, але мало велику площу, накопичивши величезні маси води з танучих льодовиків. Якщо взяти за середню глибину водойми 10 м, то виявиться, що обсяг води в ній сягав приблизно 400 км3.[5]

- ↑ Тутковський П. А. О происхождении озерных лессов. Труды общества исследователей. — Житомир, 1912. — 240 с.

- ↑ Цапенко М. М. К истории геологического развития территории Белорусской ССР в антропогеновое время // Тр. Ин-та геол. наук БССР. — 1960. — Вып. 2. — С. 12—21.

- ↑ Мандер Е. П. Антропогеновые отложения и развитие рельефа Белоруссии. — Минск, 1973.

- ↑ Л. Л. Залізняк, Полісько-дніпровська катастрофа фінального палеоліту з позиції археології, 2008

- ↑ Пазинич В.Г. Геоморфологічний літопис Великого Дніпра. — Ніжин, 2007.